Long Read | Digging into pan-African cultural memory

Digital archive Panafest – together with Chimurenga’s Festac ’77 – explores important moments in Africa’s history by reflecting on four massive political and cultural festivals.

Author:

24 March 2021

The period of decolonisation in the 1960s and 70s in Africa allowed art to flourish and nurtured an infectious spirit of pan-Africanism and public dialogue of ideas. Newly independent nations used art as a way to articulate their freedom and promote the value of African culture.

Panafest is an online platform that captures stories about four of the largest gatherings in the history of the African continent: the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres (Fesman ’66), which in those times translated to First World Festival of Negro Arts, held in Dakar in 1966; The First Pan-African Cultural Festival (Panaf ’69) held in Algiers in 1969; Zaire ’74 held in Kinshasa in 1974 and the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (Festac ’77) held in Lagos in 1977. These four festivals are still unrivaled in their celebration of African art, politics and culture

Speaking from her base in Paris, Panafest co-director Dominique Malaquais calls the platform a web cartography and a web documentary. It is an interactive archival site too and an altogether impressive body of work.

Digging into memory through 54 interviews, Panafest brings together scholars, activists, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, actors, writers and dancers who took part in the four festivals. The goal is “to memorialise and bring to life for new and for future generations the power, the complexity and the richness of these four pan-African festivals”, says Malaquais.

The project was born 10 years ago, when synchronicity brought a collective of researchers together. Malaquais paired up with Cédric Vincent and researchers in other parts of the world. Steadily, they collected information and travelled extensively to meet people who could share their experience of the festivals.

Chimurenga, a pan-African literary and cultural hub based in Cape Town, is the host platform for Panafest. While processing this research, Malaquais suggested working together with them.

Since inception in 2002, Chimurenga continues to play a central role as a publication that connects South Africa to the rest of the African continent and the global Black diaspora.

Overlaps and connections

The Panafest project research ran parallel to the Festac ’77 book Chimurenga published in 2019.

Research uncovered by Panafest reveals overlappings and parallels exist between the historic festivals when looked at collectively and with fresh eyes. Each host country and its leaders were driven by political desires, for example. Dakar ’66 was a platform for the philosophy of négritude, while Panaf ’69 celebrated pan-Africanism and liberation. Festac ’77 drew from both festivals to imagine Black solidarity.

Related article:

In a panel discussion held at the University of Chicago, Malaquais says: “The political heft of the four festivals tends to be understated in mainstream historiography. They tend to be presented as ‘just arts and culture’ events… In fact, they were powerful actors in the emergence of phenomena that significantly impacted the second half of the 20th century.”

Malaquais adds: “As meeting grounds between creators, intellectuals and political personnel on the one hand, and extremely large and varied audiences on the other hand, they provided an important way for ideas that had been previously confined to the elite to make their way into the public sphere.”

Fesman begins it all

Launched as a celebration of art in Africa, Fesman ’66 took place in Dakar, Senegal in 1966. Festival contributions included poetry, sculpture, theatre, art, film, architecture, dance and design. More than 2 000 people contributed.

It was a month-long arts festival instigated by President Léopold Senghor and sponsored by the state. The festival was an extension of Senghor’s interest in the concept of Négritude which, with Aimé Césaire, he helped develop. It is an idea rooted in the self-affirmation and celebration of Blackness and African identity on its own terms.

Delegates included important African cultural figures like the South African poet Keorapetse Kgositsile and Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka. Some came from abroad too, like Langston Hughes, William Greaves and Duke Ellington. A massive colloquium examining African art was held, bringing together intellectuals from around the world. The festival was widely praised and criticised by many. For example, by the historian Cheikh Anta Diop whose relationship with Senghor’s politics and worldview was to say the very least fraught. Kgositsile too, it must be said, was quite critical of Fesman.

More inclusion at Panaf ’69

In many ways, Fesman set the stage for Panaf, held three years later in Algiers. Though commonly seen as a rebuke to its predecessor, it was far more complex than that.

In Dakar, the invitation to participate was extended only to countries recognised by the international community, whereas in Algiers liberation movements from around the world were included. Fesman ’66’s focus on Négritude meant that much of Northwest Africa was excluded from participating. Panaf ’69, on the other hand, presented a much more inclusive festival, opening up to various nations from the region.

Algiers was dubbed “a revolutionary Mecca” when Panaf was held there in July 1969, seven years after Algeria’s independence. The festival was mandated by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1967. It ran for 10 days with a line-up of artists and radical activists from all over the world. A festival designed to be an anti-colonialist and anti-capitalist gathering, it was significant for its focus on nation-building, pan-Africanism and fighting for freedom. A rare documentary by the late Guevarist Théo Robichet shows free-jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp improvising on the streets of Algiers, surrounded by hundreds of onlookers.

Taking a leaf from Fesman, an exhibition celebrating classical and modern African art was held. There was an important colloquium too, this time reflecting on African unity. Several participants at the colloquium, notably philosopher Stanislas Adotevi, heavily criticised the concept of Négritude.

In an interview, Vincent notes: “For 10 days or so, the Panaf was the centre of a world in the process of creating itself, of discovering a sense of cultural and political pride, of belonging, and the ability to exert an influence on the world.”

The festival also brought together liberation movements from all over the world. The Black Panthers, who had in parallel set up a base in Algeria under Eldridge Cleaver’s leadership, were a big part of proceedings, for example. Other liberation movements struggling against colonial powers who were present at Panaf included Frelimo from Mozambique, the Palestine Liberation Organization from Palestine and the ANC from South Africa.

Puzzle of Zaire ’74

Largely excluded from the dominant narrative of these grand festivals is Zaire ’74.

A brainchild of then-president Mobutu Sese Seko, it would also double as a promotional event for the iconic heavyweight championship boxing match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, famously billed as The Rumble in the Jungle. Mobutu wanted this festival to have a similar feel to its predecessors. Instead, it became a three-day music festival taking place from 22 to 24 September 1974 in Kinshasa, attended by an estimated 80 000 people.

Malaquais was doing extensive research on Zaire ’74 at the time of getting involved in the Panafest project. “No one had ever talked about Zaire ’74 as it relates to the other festivals,” she says.

“What’s interesting about Zaire ’74 is that, fundamentally, it’s an act of plagiarism. Mobutu looked at what had happened in Dakar and Algiers. And he had his eye on what was going on – what was about to happen – in Lagos, because he saw Zaire as being in competition with Nigeria, in terms of representing what was the country of reference in Africa at the time. So he ended up borrowing widely from Fesman and Panaf and from the preparations for Festac. He took and remixed – borrowing or pilfering vocabulary, symbols, tropes from the two previous festivals; inviting artists who had been invited to Fesman, Panaf and Festac – and behaving, in the process, like a brilliant, if deadly DJ.”

The concert was organised by Hugh Masekela and producer Stewart Levine curated the line-up, as a way to connect with artists based in the United States. Among those who played to packed audiences were James Brown, Bill Withers, Miriam Makeba, the Fania All Stars and Tabu Ley Rochereau.

Mobutu initially sought the OAU’s permission to create what he called the second Panaf. Permission was not granted. Art and spectacle in the service of politics drove his goal of drawing the attention of the international community. He also meant to explore the festival as a manifestation of the principles of “Authenticité” under which he ruled. It was one of many ways with which he hoped to legitimise his rule.

Festac ’77’s cultural significance

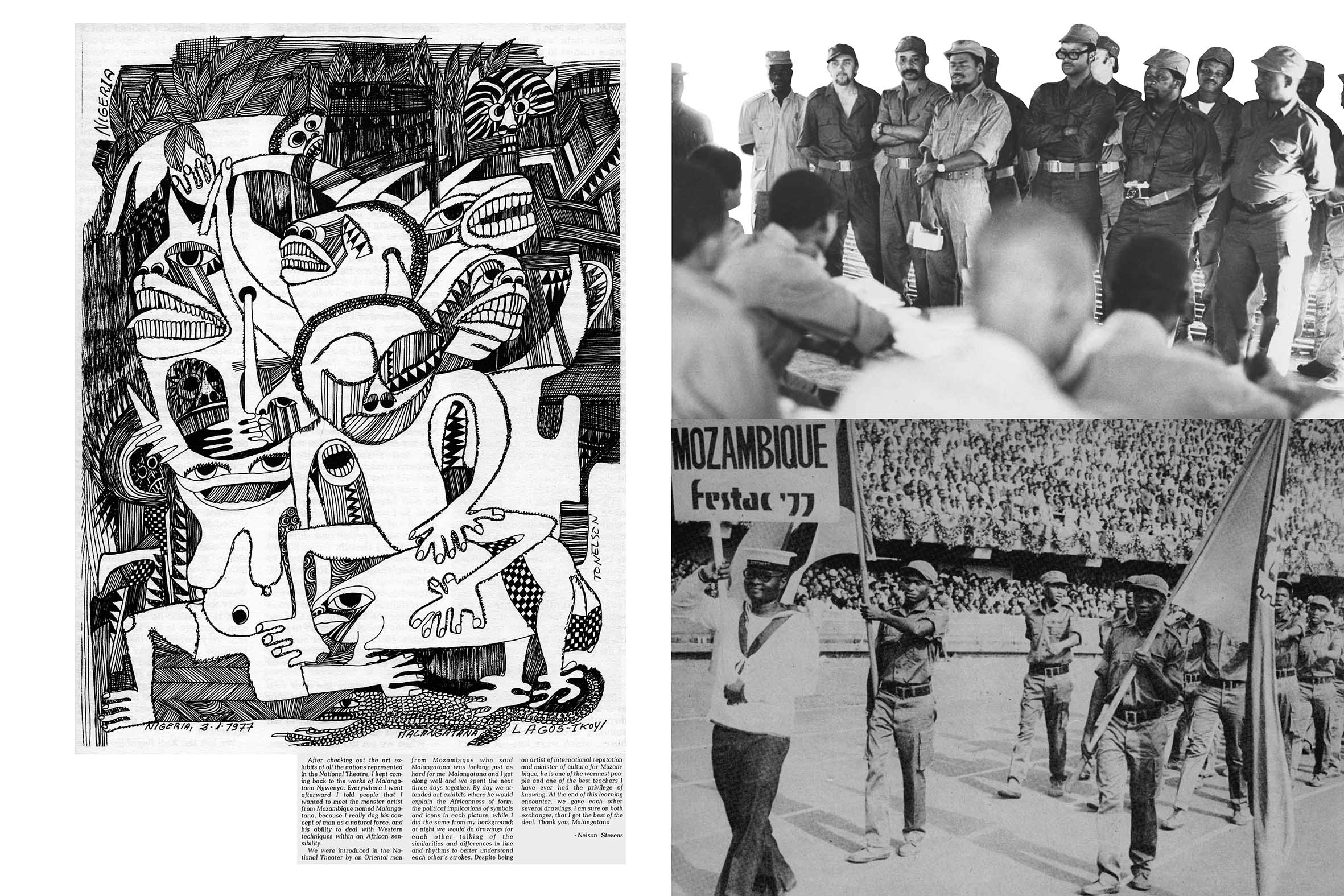

Out of all the festivals, Festac, held from 15 January to 12 February 1977, was the most lavish. It was an incredible display of Nigeria’s new oil-rich economy. Artists and scholars from all over Africa and the Black diaspora gathered in Lagos – the capital at the time – and Kaduna, in the north of Nigeria.

As in the previous festivals, huge structures were built, transforming the city into a modern hub. A massive state-of-the-art national theatre was built to stage the festival. An entire neighbourhood, dubbed the Festac Village, was created to house the 17 000 participants who arrived from 59 countries. All were guests of President Olusegun Obasanjo.

To date, it is the largest single cultural event held on the African continent. Musicians who took part include Miriam Makeba, Sun Ra, Gilberto Gil, Stevie Wonder, Franco Luambo and Bembeya Jazz National. Its core aims were to revive the promotion of Black culture and values.

The opening ceremony was a parade from participating countries. A central colloquium, theatre performances, film screenings, exhibitions and musical performances ran throughout. In the colloquium, there were discussions around what constituted “Blackness” and being African.

Malaquais reiterates that one of Festac’s main goals was “to restore the link between culture, creativity and mastery of modern technology and industrialism so as to endow Black peoples all over the world with a new society deeply rooted in our shared cultural identity, and ready for the great scientific and technical task of conquering the future”.

South African activists and artists led by the late trombonist Jonas Gwangwa performed a dramatisation of the 16 June 1976 events, in the form of music, dance and poetry. This later led to the formation of the Amandla Cultural Ensemble.

The official festival emblem was a replica of the famous 16th-century Benin ivory mask, Queen Idia’s head. The Nigerian government made an official request to the British Museum for the return of the original, at least for the length of the festival. The request was denied. This started one of the earliest conversations of restitution and return of African artefacts and works of art held by Western museums obtained illegally through colonisation and conquest – a critical conversation that continues to this day.

Chimurenga questions past and present

In 2019, Chimurenga published a book titled Festac ’77.

One question the book asks is: “Can a past that the present has not yet caught up with be summoned to haunt the present as an alternative?”

The seed for the book was planted in 2010 after South Africa hosted the World Cup. It was roughly 10 years in the making. Beyond official details, it was tough to find written accounts about the festival.

In an interview, editor Ntone Edjabe says: “This intrigued me. The people who experienced Festac seemed unwilling to write it, as if bound by an unspoken nondisclosure agreement. And so, its stories circulated in the manner of a family secret, a family of millions of people.”

But there are about 40 albums [in LP records] that exist of artists who performed at the festival. Hence, sound became the entry point through which Chimurenga began their research. In this sense, it can best be described as a mixtape.

“It refuses to be written, but is spoken, sung and performed on record more widely than any other historical event I’ve researched… Together, these LPs constitute a sound world in which the memory of Festac is as active as it is missing in print,” says Edjabe.

Hence the introduction to the book says: “…decomposed, an-arranged and reproduced.” It is a reference to the sonic aspect, along with personal and artistic encounters. It becomes a book that can be at once read and listened to.

Like with Panafest, the aim was to tell the Festac story through the words and experiences of people who were there. These later led to newspaper clippings, posters, diary pages, artworks, advertisements, essays, photographs, articles, films and home-made recordings being collected over the years. It is a book, Edjabe says, that “could only be made by many hands, page by page”.

For assembling, inspiration was drawn from Toni Morrison’s The Black Book – a collage of works arranged into one book – to allow the musicality and stories of people to shine through.

Similar again to Panafest, there is no singular and linear story told, and the book can be experienced from any direction. Reading begins where the eye lands.

It was impossible to know who was at the festival from official records, so a different approach was taken. Events were organised around the world to find more people who attended the festival. Chimurenga also looked into archival material from The Centre for Black and African Art and Civilisation in Lagos, which holds important documents and recordings of performances. Side projects like the Chronic – Chimurenga’s publication – were also used to advance the research.

A collaborative reading

Despite Fesman ’66, Panaf ’69, Zaire ’74 and Festac ’77 being important singular moments in each country’s history, there are powerful connections which tie the four events together. Malaquais notes: “There are these four moments that brought the entire African world together. And they’re all linked to each other. People, objects, music, words can be seen travelling back and forth between them.” The result, she says, is akin to a Möbius strip that keeps coming back on itself even as it moves forward and out.

Panafest’s interest lies in a non-linear reading of the festivals. It is especially interested in the highly personal accounts of those who took part and in different perspectives that it highlights, all of which are centred on lived experience.

From her research, Malaquais remembers one stand-out moment told by Koffi Kwahulé, an author who visited the festival as a young man:

“His most striking memory of Festac was of the train ride between Lagos and Kaduna. And the massive jam sessions and the partying and the poetry readings occurred on the train throughout that journey. That, to me, speaks to some of the most interesting, and least-known aspects of these festivals.”

Malaquais stresses the collectivity of the project. Those that did the research and everyone who shared their story are equal contributors. As opposed to trying to tell an organised official story, the Panafest team were interested in human details. They were interested, for example, in what it felt like to walk through the streets on a particular festival day. This meant treating everyone as equally important, no matter their experience or background. Research gathered by Panafest (everything from photographs, books, newspapers to programmes, maps, T-shirts, ashtrays, bags) is now housed in the archives of the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris.

Panafest allows us to understand how art became a vector for diplomacy, reflection and at times confrontation between newly liberated countries, colonisers and struggle movements.

“I think that what makes these festivals so exciting, is not only that these were amazing events that happened shortly after independence, but that they have very clear reverberations in the present,” Malaquais says.

Visit Panafest here and buy Chimurenga’s Festac ’77 book here.