Ngidi exposes thinly veiled racism in SA cricket

The reaction to Lungisani Ngidi’s call for CSA to acknowledge that black lives matter was unsurprising. The sport still has racist elements in its midst, including beneficiaries of apartheid.

Author:

17 July 2020

There is a moment in the documentary Fire in Babylon when commentator and former West Indian fastbowler Michael Holding considers the “honorary white” status conferred on the Caribbean cricketers who participated in a rebel tour of apartheid South Africa in 1983.

His response is unequivocal: “What is wrong with the colour of my skin? What is wrong with my ethnicity? Why should anyone tell me that I have to be an honorary anything apart from what I am? These guys have sold out, having now accepted the term ‘honorary white’. If [Ali Bacher and the white cricket establishment in South Africa] paid them enough money, they would be willing to accept chains on their ankles and it was disgusting.”

Some of the cricketers who had “disgusted” Holding included Colin Croft. He was one of the four who, with Holding, Joel Garner and Andy “Hitman” Roberts, made up the famed Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse fastbowling unit that spearheaded an all-conquering West Indies team for several years.

Others, like sublime batsman Lawrence Rowe and talented wicketkeeper and batsman David Murray, would have walked into most other international teams. But they could not represent this one because it was so good and suffered financially because of it. This was suggested as justification for touring apartheid South Africa.

The rebel tourists were handed lifetime bans from playing cricket for breaking the international sports boycott imposed on South Africa at the time, and many would return a year later to play again. They had become such pariahs in the Caribbean that some, including Croft, settled in the United States. Others stayed in South Africa to play domestic cricket, while many of those who did return home drifted into hard drugs, alcohol and itinerant lifestyles because of the ostracism they suffered.

Holding and the rest of that great West Indian team would go on to dominate international cricket for a further decade, maintaining an unbeaten Test series record until 1995 in an unparalleled run of excellence.

Along the way, the West Indians accomplished the kind of feats that not only set sporting records, but also coalesced with reggae music and Rastafarianism, Black Consciousness and Black Power to imagine a new order in both cricket and the political world: one that recognises the value of a black life – despite the oppression, subjugation, violence and targeted bigotry that life had to endure – to this day.

There was no more glorious example of this than the 5-0 “Blackwash” of England in 1984. It was the first and only time that Empire had suffered such a huge series loss at home. The victories were marked by unforgettable scenes, all set to the fiery political music of Linton Kwesi Johnson and Robert Nesta Marley.

Related article:

There was Malcolm Marshall batting with one hand because he had suffered a double fracture to his left arm. There was Vivian Richards, so potent a symbol of the political awareness in that team, giving meaning to his words: “My bat would have been my sword at that time and it’s [the racist and fascist] people who you want to put it to.”

Opening batsman Gordon Greenidge had, as a child, accompanied his parents from the Caribbean to England as part of the Windrush generation. He remembered suffering racial abuse while still a kid and being called a “wog”, a term whose meaning he initially didn’t understand.

His 214 not out on the final day of the Lord’s Test match ensured that the West Indies clawed their way back to win in exhilarating style. It also formed, he would say years later, one of his most dignified and explosive responses to his racist tormentors and the National Front fascists running around beating up people in England in the 1970s and 1980s.

Making the Empire grovel

Then, of course, there were the scenes of ecstasy and jubilation at the Oval in south London when a predominantly immigrant crowd rushed on to the field to celebrate as the West Indies wrapped up the 5-0 series win in their final match.

The Oval was just a few kilometres away from Railton Road, the front line of the 1981 Brixton riots, an explosion of anger against the British police, government and society that had tormented and degraded black communities for decades – communities who had been invited to this uninviting centre of Empire to provide cheap labour.

The West Indies in England has, ever since a 3-0 Test series victory for the tourists in 1976, come to represent more than just cricket. The actions of those men have subverted and overthrown the hierarchies and notions of master and slave that, historically, have been so fundamental to cricket and what it propagated: Empire.

Those tours have also become a symbol of black pride and reaffirmed humanity for marginalised communities in England and around the world. Their actions healed people who, for centuries, had been deemed sub-humans and slaves.

For black cricketers and children in South Africa during the 1980s – a time of states of emergency and ramped-up government violence against internal anti-apartheid protests – Holding, Marshall, Richards, Greenidge and the like were powerful symbols of what was possible when the white man was overthrown.

So when Test cricket finally resumed last week in Southampton, after months of inactivity caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, it was fitting that the two teams who most aptly represented the historical struggle of good over evil would be taking the field.

Related article:

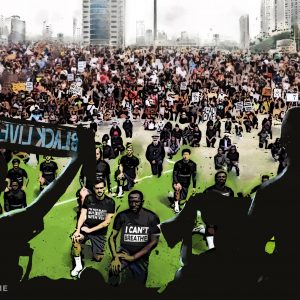

The sight of Jason Holder’s West Indians taking the knee (together with their England counterparts) in support of Black Lives Matter, black-gloved clenched fists raised in the air to echo the 1968 Olympic winners’ podium Black Power protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos, lifted spirits around the world. Their actions suggested that whatever inequalities and inequities the pandemic continues to expose, an honourable human spirit will always strive for justice.

Likewise the words of Holding and fellow commentator Ebony Rainford-Brent, the first black woman to play international cricket for England, who both talked so eloquently of the structural racism they endured over their careers.

It would seem only natural that, considering South Africa’s racially divided past, Proteas bowler Lungisani Ngidi would, in that same week, use being named Cricket South Africa’s (CSA) one-day international and Twenty20 international Cricketer of the Year to call for the organisation to show support for the Black Lives Matter movement when domestic cricket restarts on 18 July (in a gimmicky new format).

The CSA’s (first) underwhelming response

Ngidi is an upstanding young man who had to bridge the class divide to fulfil his cricketing potential. His background, impoverished but assisted, informed his call for the support of Black Lives Matter.

But CSA director of cricket Graeme Smith’s response to Ngidi’s call was lukewarm and indicated an inability to fully understand the trauma and suffering that black South Africans have and continue to experience. A scion of privilege, is it any wonder that Smith saw no wrong to right, and nothing wrong, when appointing so many white former players to the Proteas management structure last year?

Related article:

Perhaps his call for a “sincere” engagement on Black Lives Matter will extend to the CSA introducing a real development programme aimed at democratising the sport in black communities. Ngidi was lucky in this regard, as so many young black cricketers from communities that have played the sport since the late 1800s and early 1900s – in the Eastern and Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal especially – have not had the opportunities he did. This is mainly because the CSA still relies on an elite schools system, rather than proper outreach and skilling focus in townships and rural areas, to produce black cricketers for the national team.

Perhaps. For, as yet, the nation still waits on him to introduce his blueprint for the game from grassroots level upwards. Or perhaps Smith is one of hundreds of thousands of white South Africans who still hold on to the fallacy that there is no history of cricket among black communities in this country, despite evidence to the contrary that goes back to the early 1890s.

The belittling and bigoted responses to Ngidi from former South African cricketers, including Pat Symcox, Boeta Dippenaar, Brian MacMillan and Rudi Steyn, exposed their own racist upbringings and the untransformed mindsets that continue 26 years after the end of apartheid.

Symcox is a known racist who, together with Paddy Upton and Fanie de Villiers, attacked South Africans of Indian descent for supporting Pakistan during a match at Kingsmead in 1998. On social media, he suggested Ngidi should focus on farm murders rather than the murder of black people in South Africa. It is a remark that remains utterly oblivious to the statistics that more black farm labourers are killed or tortured on farms than whites.

Dippenaar took to social media for an American alt-right-influenced rant against Black Lives Matter for being a “Marxist” organisation hellbent on destroying the family unit. He then patronisingly suggested that Ngidi read the work of Milton Friedman, the Chicago School economist who preached the trickle-down capitalism embraced by former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and then-US president Ronald Reagan in the 1980s – and more latterly by the ANC in South Africa.

Dippenaar, it would appear, is unable to draw a line joining Friedman and those economic policies to the rapacious capitalism that has subjugated black men in this country to nothing more than units of labour to work on the gold, diamond, coal and platinum mines. He appears blind to the consequences of these policies that result in a nefarious relationship between the state and mining companies and, eventually, events like the Marikana massacre.

Dippenaar is certainly blind to the fact that the South African police murdered 34 black human beings on 16 August 2012 in Marikana. That those deaths were completely avoidable. That those lives mattered to the families and friends left behind. And that millions of (black?) South Africans were left aghast at how this was allowed to happen in a democratic country that had promised, in its Constitution, to never let it happen again.

Racist principles that went further than 1994

All the vitriolic responses by former players to Ngidi also exposed a rainbow nationalist reconciliation project that, while succeeding in allowing Symcox, Dippenaar et al to participate in international cricket after South Africa’s return in 1990, has still not forced them to look beyond themselves, their racist ideas and their white privilege.

All these elements, in fact, acted to allow Symcox et al to have mediocre careers protected by white media and white cricketing bosses who have obstructed transformation at every turn from 1990 onwards.

Dippenaar departed Test cricket with an internationally substandard batting average of 30.1, white mediocrity that went unquestioned by the white-dominated media, who railed against black “quota players” being included in the South African team over that same period.

An alleged allrounder, Symcox’s batting average was 28.5, his bowling strike rate was 96.2. Holding’s bowling strike rate was 50.9.

Whiteness, and its racist principles and ideas, were allowed to endure in South African cricket well after the end of apartheid. To succeed in South African cricket – as a player, administrator or journalist – has meant assimilating into the establishment. It has meant becoming an “honorary white” to whatever degree your conscience allowed you.

Which is why former Proteas Test batsman and current coach of Western Province Ashwell Prince went on to social media last week to talk about his experiences of racism while playing international sport.

Prince talked of black members of the team experiencing racism during a 2005 tour of Australia – when Smith was captain – and being asked to ignore it and get on with the game by the team leadership and management.

“Our system is broken,” he stated. And it certainly is. From current cricket suits and former cricket players to cricket writers, one of whom, in response to Prince’s tweets, said that the only people to blame if the system were broken would be black administrators as they were the “majority” on the CSA board.

It is a view that goes to the very heart of white blindness – one that refuses to see and understand the internal obstacles placed in the way of black cricket administrators like Krish Mackerdhuj from the early days of unification until more recent times.

A blindness oblivious to the politics that was being played by white administrators hellbent on continuing to maintain their privileged position at club, provincial and national level from 1990 onwards – to the detriment of black cricket development in this country.

A blindness that refuses to concede that the malaise in South African cricket is the making of these historical attempts to maintain white supremacy in the sport that, with the Gupta family’s political and financial incursions into cricket in the 2000s, deviated into forms of capture.

This sickness currently manifests itself as the Fanonian nightmare of the current board, filled with self-serving and inept administrators, reproducing the methods and the madness that go back decades, to the rebel tours and beyond.

For cricket in South Africa to truly transform, it requires a proper truth-finding process. One that interrogates the roles of those, like Ali Bacher, who organised the rebel tours of racist South Africa through to the white mercenaries involved in the deplorable Hansiegate match-fixing scandal and the Guptas’ influence in cricket, to the current moment where black administrators who are not interested in giving the sport life and meaning in black communities are running the game.