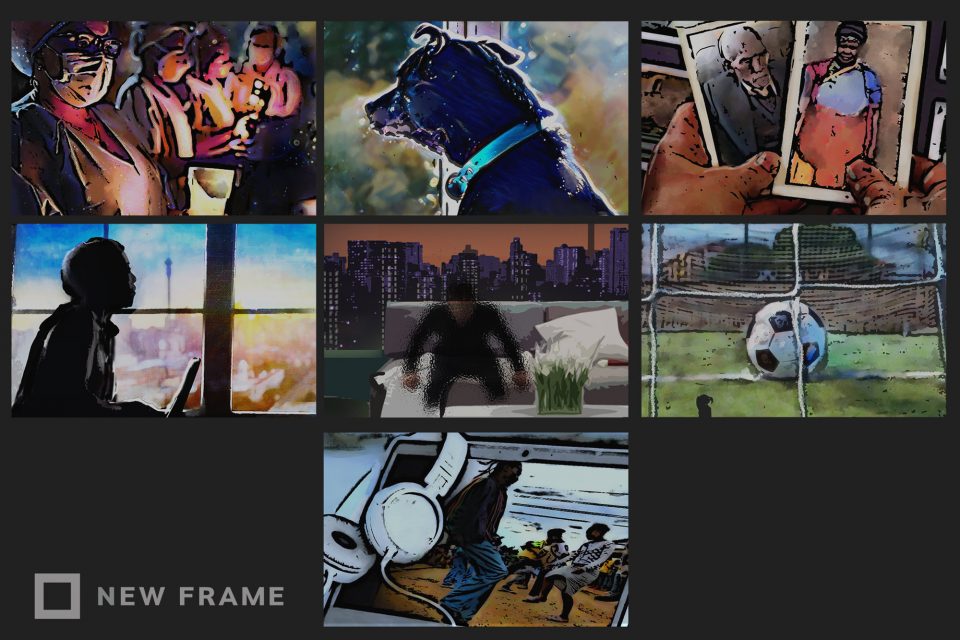

What Covid-19 robbed us of in its first year

The pandemic has taken much: loved ones, livelihoods, sanity and life as normal. A year after the start of the initial lockdown, New Frame staffers share what they’ve lost – from lighthearted to se…

Author:

26 March 2021

Documenting the pandemic

At the beginning of the South African government’s Covid-19 lockdown, work for journalists like me continued as usual. The only difference was that we wore masks and gloves, sanitised our hands constantly, and had to entertain children at home between writing stories. But as the days passed, most stories became about frontline workers who had died needlessly because they had little or no personal protective equipment. It was devastating to visit small clinics and hear that most of the nurses, community health workers and security guards working there had contracted Covid-19 and several had died.

Standing in clinic car parks at physically distanced, candlelit memorials for three or four nurses at a time would have been unthinkable before the coronavirus pandemic. But it became normal. At some point, friends and family began contracting the virus, too. I was being contacted all day with stories of Covid-19 deaths in hospitals that had run out of oxygen and did not have enough ventilators, and of hospital pharmacists forced to continue working while awaiting their test results. Knowing all this while family and friends were falling ill and being admitted to hospital was extremely worrying. For the first time, I wished that I didn’t have any inside information. – Anna Majavu

Losing companions without realising it

Shortly before the initial lockdown in March 2020, my then 12-year-old border collie cross Labrador, Oona, slowed down. A lot. From two daily walks totalling up to three hours a day, we barely managed to enter the park before Oona sought to sit and lie down on the nearest patch of soft, inviting grass.

Her lifetime hip dysplasia, regardless of all the medical supplements she had been on since a puppy, had taken hold, grimly. Then, worse: a severe seizure and every three months or so, another. More medication, less mobility for her.

Lockdown – hard, soft or in-between – was all one to us. We stayed at home, secretly happy not to be out on frosty winter mornings or having to wait until summer heat had turned to cool and shadow after six o’clock on Highveld days.

We began to know a house from which we’d been absent in the promise of morning and the comfort of twilight. It was the next best thing to walking and yet we lost so much: for me, the company of friends, acquaintances, colleagues; for her, companions and playmates that I don’t think she will see again. – Darryl Accone

Not being able to say goodbye

For the first time since relocating to Johannesburg in 2020 from the Western Cape, I did not visit home because of the Covid-19 nationwide lockdown. But what was even more stressful was the thought of losing my parents to the coronavirus, or any of my family members, and not knowing if and when I would see and reunite with my family again. Not seeing them and worrying about losing them to Covid-19 made living unbearable. I found myself experiencing Covid-19 anxiety. Amid this coronavirus worry, I lost my grandparents in the middle of last year. It hurts that I could not attend their funeral. I didn’t get a chance to say goodbye. – Zandile Bangani

Principles versus entertainment

The initial lockdown period was terrifying, not only because of the uncertainty around the coronavirus and hyper-militarised approach from our government but also the fact that we had to let go of what human existence is built on: physical, human interaction. For almost four months I could not go home to KwaZulu-Natal, in part because of the lockdown restrictions and also because I feared deeply that I would place my family at risk, particularly my father who is in his late 60s.

I had to adapt quickly to the “new normal” of “working from home” without much in-person interaction with my colleagues and friends, to whom I am deeply indebted for continuing to make space for me. The worst was not being able to participate physically in the burial of relatives. There were important cultural customs that had to be postponed because of the lockdown restrictions.

Also, for the longest time I have held the view that owning a television is unnecessary. However, when one could not watch football in a public space like I used to, I had to review this position. “One cannot be a slave to his own principles,” I said to myself. But despite the need for television, I have not betrayed my principles and remain televisionless. – Musawenkosi Cabe

The importance of friendship

It feels strange writing about what I’ve lost during the Covid-19 pandemic when so many experienced profound loss. People lost their lives, people lost family members and friends, and people lost their livelihoods.

For me, it’s been the smaller things. And they’re insignificant when compared with the trauma many people have had to live through in the past year. But it’s been things such as embracing my parents, or sitting close to people whose company you enjoy in a bar until the last round is called. It’s been the casual friendships developed at indoor, six-a-side football, and at the gym.

The Atlantic quoted neuroscientist Mike Yassa saying: “We’re all walking around with some mild cognitive impairment.” And I’ve felt that myself.

It’s been walking over to the kitchen and forgetting about what I wanted to do, or leaving the house and realising I don’t have my car keys. It’s been time that’s becoming confusing, with days and weeks merging into each other with memories feeling both so recent and so long ago. Besides the profound loss experienced by so many, we all lost a little bit of sanity and a little bit of the casual friendships that we never knew we relied on so much. – Jan Bornman

The great sport divide

One day, someone is going to bust me on the scam I have been able to keep up for years. But before that happens, I will make the most of it. Somehow, I have managed to get by and be paid to watch sport with football my undisputed first love. How no one has picked up on this scam is beyond me. I am like the player Eduardo Galeano wrote about in Football in Sun and Shadow who is the “envy of the neighbourhood” because I get “paid to have fun”.

But when Covid-19 hit, that fun stopped. Sport, like every sphere of our lives, ground to an abrupt halt. Without sport, which is both a job and an escape, the television only held grim news of death, job losses, trigger-happy law enforcement officers killing people in their homes and leaders who saw this virus as a political weapon.

Sport eventually returned, at first with no spectators although they were slowly allowed back into stadiums in countries that had done enough to curb the spread of the coronavirus, or countries whose leaders were in denial about the devastation caused by the virus so they politicised masks and large gatherings. While I am grateful for televised sport, once the novelty of having it back had waned I realised that it just doesn’t feel the same.

This made-for-television product feels like going from a gourmet meal to eating microwave food, and SuperSport’s sport monopoly adds more salt to an already bad meal. I watch because it’s my job. And while social media brings us together, there is still a huge divide. The majority of the South African public, unable to afford pay-television, is fed scraps on ailing SABC channels with no option to go to the stadium. – Njabulo Ngidi

Turning back the clock to go to ‘church’

I took the Uber southeast out of Johannesburg early in the afternoon of Sunday 15 March 2020 for what was to be my last “church” service. Well, my church is not a conventional one. Its congregation roves across East Rand townships, its sacraments of reggae blasting from pulpits of stacked speakers.

As we arrive, deejays on decks are already preaching to the dancing converted in the open veld in Dikole Section, Katlehong.

“Let’s welcome Ntate Charles!” my friend Giggs bellows over the mic as I start my set, loaded with roots reggae favourites: Police and Thieves, Pass the Kouchie, Inglan is a Bitch, Two Sevens Clash, Blood and Fire and Night Nurse.

I’m the musical equivalent of a lay preacher: an amateur selektah who shouldn’t give up his day job. But I occasionally get it so right that it’s almost spiritual, transcendental. Like that Sunday afternoon.

Driving into the setting sun on my way home, a melancholy descends on me like a heavy blanket. That evening, President Cyril Ramaphosa declares a national state of disaster to curb the spread of Covid-19.

It’s a year on and I miss that colourful, welcoming congregation, the sweet smell of ganja, the fist pumps, the rhythmic reggae line dances. If you play the right song at the right time, dancers will do the spinning signal with their index fingers, for you to rewind the song to the beginning.

If only I could rewind life back to that time: free and unrestrained, but forever lost. – Charles Leonard.